Summer Program 2013-Week 1 Update

The First Weekend: Reception and Revealing the Topic

The first week of the summer program has flown by. Over the first weekend, the students got to know each other and they got to know the Compass Project.

The Summer Program topic was revealed on Saturday as “How can we tell what direction sound comes from?” Our students began trying to answer this question by designing simple experiments they could use to gain some intuition about the question. At the end of class on Sunday, the students had decided that the first thing to do would be to define “sound” and understand its properties.

During the Metacognitive class, students began to think about scientific models. They also talked about the “Compass Classroom” and how learning in a classroom based on group work and student discovery can be beneficial.

The First Week: What is Sound?

Today was the day that the students really got to work on defining and understanding what sound was. During the experimental class in the morning, they explored and build musical instruments that vibrated to make sound. Then, they built a model of sound that connects what is going on with the individual atoms in the air and the different noises and pitches that we hear.

During some free time before dinner, the Compass Students played some Ultimate Frisbee!

Academic Coordinators from Physics, Astronomy, and Earth and Planetary Science visited to tell our students a little about their departments.

On Wednesday, we hiked to the “The Big C.” There are great views of the East Bay and SF from there.

Towards the end of the week, students build their own speakers, looked at music and voices as both waveforms and frequency plots, and developed a model for how sound travels and interacts.

Want more pictures? Check out the album!

Creating Together in Compass: Strategies To Support Participation

Introduction co-written by Gina Quan and Angie Little

In this blog we discuss the development and implementation of organizational and classroom strategies around fostering participation.

Broadly, Compass is a place where we work on improving undergraduate education in the physical sciences. We work on challenging organizational and physics problems together. One of our design goals for our classrooms and organizational meetings is participation. Underlying this goal is the value that the more people who participate, the better and richer are our conversations, decisions, and creations. We believe that every member of a discussion can contribute something unique from their individual experiences. For instance, one of Compass’ strengths is the role of undergraduates and graduate students as co-leaders. Although Compass was founded by graduate students, the undergraduate leadership’s perspective has been central in continuously improving Compass to better meet the needs of students in our classrooms and programs.

Discussions and group problem solving are central to the Compass classroom and organizational structure. Compass classes are modeled after best practices in scientific research. In small and large groups, students focus on open-ended scientific questions about physics models and measurement (such as exploring the ray model of light or measuring thermal expansion). We also explore important questions related to college life, study habits, and how to measure learning and growth. More details about this can be found on our website or in this 2012 paper.

As an organization we operate on consensus decision-making. Because Compass is in a process of continual refinement and progress, it’s important that our members have a say in major decisions affecting how the organization operates. The day-to-day functioning of the organization is done in small groups of undergraduate and graduate students, while major decisions for the organization (such as “should we apply for an NSF grant?”) are decided by consensus at our monthly meetings. After a proposal for a major decision, the proposal is amended and discussed until everyone agrees.

In trying to create a space that is friendly and open, we have employed many types of strategies over the years to encourage participation. Core to Compass is building community through spending time together outside of a physics classroom setting. We’ll get more specific about what happens during community building time and how we see direct implications for participation in more formal contexts like our classrooms. We will also discuss jargon buzzers, a classroom tool that we’ve found to be particularly impactful.

We see these strategies as important strands in the fabric of a larger classroom and organizational culture that was cultivated by the undergraduate and graduate students involved. We’re not sure how they would stand alone when added to a new environment, but if you also share our values, we hope they help you in generating related strategies that work in your own context.

The Story of the Jargon Buzzers

In our first experiences teaching for Compass, our students often tossed around a lot of science jargon terms that they had picked up from high school that their classmates (or often they themselves) didn’t really understand. As instructors, we would frequently challenge students to unpack jargon, but wanted the students themselves to become more self-aware of their jargon use and to hold each other accountable to explaining ideas. We also wanted to make sure they felt comfortable asking instructors for clarification. To put the power in the hands of the students as well as to make more of a fun game of challenging each other, we introduced something called a “jargon buzzer” to the classroom in 2010.

Jargon buzzers are, simply, any object that makes a buzzing noise that can be placed at every table of 3-4 students (for instance, a buzzer from the game Taboo, as show in the photo). Our first jargon buzzers were simple, made of cheap parts from the local Radioshack, and housed in altoids tins.

We started using jargon buzzers consistently during the entire Fall 2010 Compass course. Instructors put a jargon buzzer at each student’s table and told everyone the idea at the beginning of class: if any person in the class used a word that you didn’t understand, you could press the buzzer and “buzz them.” Instructors were no exception; in fact, co-instructors would often buzz one another to support the students in feeling more comfortable doing it. The first day that we used the buzzers we tried to do a lot of buzzing to get everyone comfortable. Students laughed at the silly noise it made . Refraction? *buzz* Snell’s Law? *buzz* Big words were no longer things that you had to feel bad that you didn’t understand. Students could buzz a classmate and the classmate would often realize that they didn’t really understand it either. Once students began realizing that other students didn’t fully understand these words or were at least willing to explain them, big words weren’t such a big deal. Now, I don’t mean to say that we were able to completely erase the scary feelings that can happen when you feel like someone in your class knows a whole lot more than you, but it seemed to help students feel much more comfortable.

Ana Aceves, a student who took the class and is now a junior astrophysics and media studies major and Compass leader, reflected on the jargon buzzers: “It became more of a ‘we’re learning together’ attitude instead of a competition to see who knew more. If I remember correctly, there was a big sense of competition at the beginning as well; people wanted to show off how much they actually knew. The jargon buzzers seemed to solve that a bit. It made it more clear that not everyone knew what others were talking about.”

Another reason we believe that the jargon buzzers had a big impact was that they made calling out jargon use feel more like a game, more playful. A colleague who studies play in education mentioned that the jargon buzzers reminded him a lot of tools from improv that he had used in his own classroom to help students feel more comfortable messing up around one another. Aceves noted that, “for me, it was also like ‘I want to be the first to buzz that word!’ or ‘How many words can I buzz today?’ It was a lot of fun, and you learn a lot in the process.”

Hikes, Shared Meals, and Road Trips Together: The Impact on the Classroom and Organization

In Compass we aim to bring more personal connections to the classroom and organization. Working on hard problems requires vulnerability and in doing something hard, people inevitably mess up and won’t have all the answers. Yet, many spaces feel intimidating difficult to participate. We encourage participation by doing both life and physics things together and by practicing problem solving more informally outside of the classroom. We don’t expect everyone to become best friends with one another, but we seek to expand our perceptions of people past simply “physics knower” to be more multi-dimensional.

When people ask what sorts of things are important to Compass, Angie likes to use the phrase that we “brush our teeth together.” Compass starts with freshman students staying in Berkeley’s dorms for two weeks together. In addition to learning about physics, they do in fact get to brush their teeth together, take windy road trips up mountains to observatories, sing silly songs under the stars, get lost on hikes, and generally live life together. Similarly, Compass tries to have at least one retreat each year where people in the organization stay at a hostel a few hours away, cook and share meals, share life as well as organizational development, and yes, brush their teeth together.

Figuring out how to climb walls together was one way that our community grew during the summer program.

When people know each other outside of the classroom, it can be easier to ask, “hey, I don’t get what you mean by that,” or to choose to help someone out if they don’t understand something. This casual time also supports opportunities for low-stakes informal problems to solve together. Gina reflected that some of her earliest Compass bonding was while learning how to climb up the hallways of the dorms, which is safer than it sounds: “I remember Geoff and Alex figuring it out and then teaching the rest of us. Getting the rest of us up the walls was certainly a challenge, and those who had figured it out coached us through the process. By the end, we had developed several different ways to climb up the walls and invented our own game of wall wrestling.” Spending free time with people can grow a community. These small activities, no matter how mundane or ridiculous, give us a sense that we create together, we laugh together and we figure things out together.

Conclusion

In this blog post, we’ve outlined some concrete strategies to create spaces where everyone feels comfortable participating. This directly follows from our values: in the classroom and the organization, we’re working on interesting, hard problems together, and everyone’s diverse experiences and skills can offer a unique and important contribution. We hope that this discussion will support you in developing strategies appropriate to your values and contexts.

A big thanks to folks who gave us editing feedback in writing this blog: Lauren Barth-Cohen, Dimitri Dounas-Frazer, Jon Bender, and Bruce Birkett, as well as many students from the 2010 Compass course who gave thoughtful reflections about their experiences with the jargon buzzers.

Behind the Scenes: Part 2

This is the second in a continuing series on real world skills that volunteers have developed through working with Compass. Read the first post here, written by Nathan and Josiah about technical aspects of managing a large and dynamic group, like creating a website and coordinating the server and mailing lists. In this post, I’ll talk a bit about fundraising.

The last couple of years I’ve been working to help raise funds to support all of the programs Compass runs. This has proceeded along a few fronts. First, we have applied for several grants. Some of these grants have been to national or local charitable organizations who fit in with our mission of supporting innovative science education and diversity in the sciences. Others were to various “in-house” programs at Berkeley that have funds to support student groups, new classes, etc.

Writing grants is a long and detail-oriented process. Aside from the obvious — potential funding for Compass — the main benefit for me personally has been that each grant application forces you to crystalize in writing exactly why Compass exists and how it is beneficial for the various populations it serves. Compass is amorphous and a bit of a moving target, and so these thought exercises provide valuable clarification.

Another important source of funds has been our summer fundraiser, in which we’ve asked friends and family of Compass to chip in a little bit to keep our summer program running. Josh Shiode and Nicole Carlson organized the original fundraiser in 2011, and I helped to carry on the work last year. Initially, I was not at all comfortable directly asking — or begging, some might say — for money. But once I mentally reframed the fundraiser as merely describing the merits of Compass to potential donors, I became much more comfortable with the work. The fundraising process has also been useful for the organization, as we now have a scalable system for keeping track of our contacts and donations, largely thanks to Josiah.

All in all, I’m proud to have done my bit to help keep Compass moving, and the main reason I’m involved is because I think Compass is valuable and important. But it’s also personally rewarding, and developing these kinds of skills is one of the reasons why.

Behind the Scenes: Part 1

By Nathaniel Roth and Josiah Schwab.

Nathan writes:

I’m a graduate student in the Berkeley physics department, and I’ve been part of Compass since the summer of 2010. One aspect of Compass that all of us are very proud of is the fact that our organization is run almost entirely by students. This includes not just our classroom activities and social events, but all of the administrative and logistical tasks to keep a community with hundreds of members organized. This is the first in a series of blog posts in which Compass volunteers will talk about some of the skills they have learned outside of the classroom and the lab as they have worked behind the scenes to keep Compass awesome.

For example, Compass maintains its own web server to handle tasks such as hosting the website and managing the organization’s mailing lists. The most valuable non-pedagogical skills I have learned during my time in Compass have been related to web server administration.

During the Fall of 2011, the Compass technology team made a decision to rebuild the server installation from scratch to improve its sustainability. This was no small task, and at the time, I had virtually no experience in anything like it. For instance, I barely knew what Apache was, the core software at the heart of many servers including our own. Fortunately, I was in the company of talented volunteers such as Allen Rabinovich, Joel Corbo, Josiah Schwab, and Abhimat Gautam; I learned a great deal through their example.

Over the course of several weekends, the five of us huddled together with our laptops and plugged the software together piece by piece. Allen, Joel and Josiah showed me how Apache is configured and how to debug common some common problems that might arise. Josiah took the lead on installing the program Mailman to manage our email lists, a task that was far more intricate than I had imagined. Abhimat spearheaded the wordpress installation that powers our website, using a theme that Allen worked hard to optimize for us. I was tasked with re-assembling our organization’s wiki (powered by FOSwiki, www.foswiki.org). All of these tasks were inter-related to varying degrees, and in the true Compass spirit, we worked together, learning by doing.

Josiah writes:

I’m also a graduate student in the Berkeley physics department, and I’ve been part of Compass since 2010. As Compass has grown, we have had to deal with new data in new ways. One of the major changes has been our transition to a funding model that has a large donor base. A big part of fundraising is making sure that we have thanked our donors and that we are able to keep them up-to-date with the activities of Compass (for example, by mailing them our newsletter). During the 2012 summer fundraising campaign, we decided that we needed a better way to keep track of those who have donated to Compass.

We wanted to move to a centralized donation-tracking system that we could use for many years to come. I constructed a simple web-based application that helps us to manage this information. This gave me a chance to try out the Python-based web framework Django. This was my first time seriously using Django and not only did I learn a lot, but I had a lot of fun. Nathan helped out by writing a python function that would parse the automated emails we receive when donations are received and would pass this information along to the database. The second generation of this system is currently under development and will allow us to keep better contact with our alumni.

Back from Sacramento: The Fall Retreat

Compass had our 2nd annual fall retreat up in Sacramento the weekend before Thanksgiving. Retreats are an exciting time where we can spend time together building community and talking deeply and broadly about the things which are important to us, so that we can all be a little bit closer to being on the same page. I was personally excited about being a part of envisioning some long-term goals for Compass. I’m always coming up with schemes, and the retreat serves as a place where everyone has come to think about Compass, and so schemes and thoughts are valuable rather than distracting.

We started off with a tradition, called “Story time with string”. When I read this on the agenda, I’m thinking to myself “Great, a corny community building activity.” But shame on me for doubting Joel and Josiah’s planning, because story time was fun and relevant to the goals of the weekend. We created the compass lineage using a ball of yarn, where people were passed the ball of yarn by the order which they had joined Compass. I learned about everyone’s histories as the yarn unraveled, and the connections which people had to one another, and the places where people had opportunities to work with one another made the history of Compass a much more coherent thing. It also made the story of Compass into a story of people. When we were done, the web of yarn was fun to play with, but it also doubled as a metaphor, partly for the breadth of our impact (when we move our yarn, everyone feels it), but also for the continuity of an idea that brings us all together.

That night, we got a chance to walk around Sacramento in the rain. It was some quality time with people who I rarely get to see in a context wich is not work related. Part of why I like Compass is because I like the people in Compass. Getting social time was really great. Dimitri gave us an awfully tricky puzzle with forks and cups that we failed to solve. I shook salt on many things. A good time was had by all.

The next day was packed with purposeful activities, and everyone was totally on board the whole time. If you’re a Compasseer, you can read about what went down on the wiki! What inspired me about the retreat was how many great, clever people are able to get together in one place and actually work to solve some really abstract problems. Diversity of opinion is really what makes this group wonderful to work with. I can be sure that there will be some level of disagreement about anything which comes up, and there will also be miscommunications when people who have very different conversational and mental types try to come to agreement. But through this, everyone gains a broader view on the issue or solution being proposed. No one owns the floor. No one gets left out. Somehow, sensibility trickles up from the chaos, and I attribute that to the cooperativity and sharpness of the people who are attracted to Compass.

Some of the things I’m most excited about which came to my attention that weekend are emerging collaborations with programs which are similar to Compass at other institutions, kick starting publication of a whole range of useful documents, and trying out a new team structure to help with internal organization. Being a part of Compass is a real pleasure!

Measuring Growth, Part 2: Self-Evaluation in Compass

One student symbolized their growth with a hummingbird for three reasons. (1) According to the student, the hummingbird is “special in its ability to hover” which “embodies the moments over the course in which I felt . . . ‘stuck’ in my studies, unable to propel myself forward.” (2) The hummingbird can also “fly in any direction, including backwards. . . . The second midterm, for example, was my fall backward.” (3) On a more positive note, the student compared their growth to a hummingbird that “elevates and flies over ground, ascending over obstacles and any problems.”[/caption]

One student symbolized their growth with a hummingbird for three reasons. (1) According to the student, the hummingbird is “special in its ability to hover” which “embodies the moments over the course in which I felt . . . ‘stuck’ in my studies, unable to propel myself forward.” (2) The hummingbird can also “fly in any direction, including backwards. . . . The second midterm, for example, was my fall backward.” (3) On a more positive note, the student compared their growth to a hummingbird that “elevates and flies over ground, ascending over obstacles and any problems.”[/caption]

Introduction

This post is the second part of a two-part story about how Compass encourages students to measure their growth according to a rubric of qualitative skills (which can be found here). The rubric that Compass uses is an adaptation of two rubrics developed by Jon Bender. How Jon developed his rubrics is the subject of the first part of this story, and can be found here. Compass’s rubric is very similar to those created by Jon, and a helpful description was given in Part 1:

These rubrics include a bunch of qualitative behaviors and skills, e.g., persistence, communication, skepticism, and self-compassion. They can be used in two ways: (1) by teachers to provide feedback to students, and (2) by students to evaluate themselves. Jon has taken both approaches, whereas Compass uses the rubrics primarily in the context of student self-evaluation.

In order for students to gain a rough understanding of the skills, each skill is accompanied by a list of defining questions. For example, one of the questions that accompanies “persistence” is: what do you do when you’re frustrated? A particular student’s proficiency can be ranked as either beginning, developing, or succeeding according to the rubric. The stages of proficiency are described through qualitative statements. For instance, the rubric characterizes the beginning stages of persistence by the following statements: I tend to try one or two things; and, I give up more easily than I should. On the other hand, succeeding at persistence is characterized by look[ing] for new ways to think about a problem.

In this post, I discuss how and why Compass started using Jon’s self-evaluation rubrics in our courses and I describe how we adapted the rubrics to serve our needs.

Measuring Growth, Part 1: Origin of the Self-Evaluation Rubrics

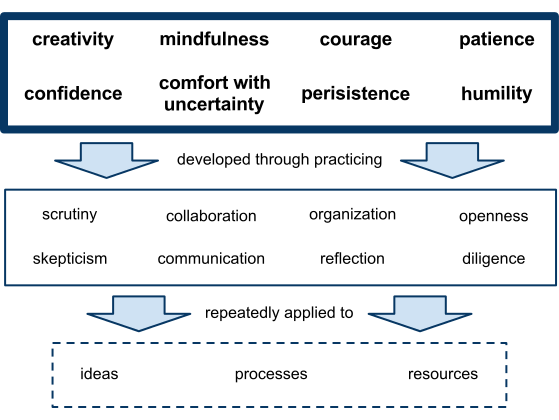

This is one of the early documents that later evolved into the status rubric. Character traits (top level) are developed by practicing skills (middle level) in the context of developing ideas and using scientific processes (bottom level). Major learning goals include developing traits and skills useful for scientific thinking. This happens in a classroom characterized by respect for individuals and ideas.

Introduction by Dimitri Dounas-Frazer

This post is the first part of a two-part story about how Compass encourages students to measure their growth using tools developed by Jon Bender, a former Oakland middle school teacher who has since moved away from the Bay Area. Jon’s training is at the high school level, as is most of his teaching experience. His background also includes teaching courses at the University of Alaska Anchorage and through CalTEACH.

In Fall 2011, Jon shared with Compass two rubrics that he developed for measuring his students’ growth: the status and progress rubrics. These rubrics include a bunch of qualitative behaviors and skills, e.g., persistence, communication, skepticism, and self-compassion. They can be used in two ways: (1) by teachers to provide feedback to students, and (2) by students to evaluate themselves. Jon has taken both approaches, whereas Compass uses the rubrics primarily in the context of student self-evaluation.

In order for students to gain a rough understanding of the skills, each skill is accompanied by a list of defining questions. For example, one of the questions that accompanies persistence is: what do you do when you’re frustrated? A particular student’s proficiency can be ranked as either beginning, developing, or succeeding according to the rubric. The stages of proficiency are described through qualitative statements. For instance, the rubric characterizes the beginning stages of persistence by the following statements: I tend to try one or two things; and, I give up more easily than I should. On the other hand, succeeding at persistence is characterized by look[ing] for new ways to think about a problem.

In this post, Jon shares with us the rubrics’ origin story by outlining the history of their development. In a following post, I’ll talk about how the rubrics have been adapted for use in the Compass classroom.

Without further ado, here is Jon’s post.

Read more >>

The Sweet Life of Undergraduate Research

I was introduced to research by my very own Compass mentor Anna Zaniewski. It just so happened that my interests in physics matched her research area, so the summer after my freshman year, I started volunteering in Professor Alex Zettl’s lab and helping Anna make solar cells. I was hooked! I loved getting my hands dirty and seeing classroom theories work in real life. I only had one introductory physics class under my belt at the time, but was assured that it’s totally cool to be a non-expert going into a new project. The whole point of undergraduate research is to be introduced to a lab environment and learn some new and interesting science. Like Anna mentions in her blog post, the graduate students you will be working with expect you to ask lots of questions, so ask and learn away!

While I continue to work in Professor Zettl’s lab during the school year, I also participated in research opportunities at other universities during the summer. The Cal Energy Corps took me to Hong Kong to research plastic solar cells, and as a National Nanotechnology Infrastructure Network REU student, I worked at UT Austin making a tiny microphone. These experiences were eye-opening, both inside the lab and out. Not only did I get to throw myself into research projects and learn about topics I had never even heard of before, I also got to interact with an amazing cohort of mentors and peers and explore some fabulous cities. I would highly recommend applying to summer research programs if you’re interested in: seeing what grad school is like, experiencing the research environment at another university, traveling and summer-vacationing and cool-people-meeting and cutting-edge-science-learning all at once. Many programs offer paid summer internships (the ones I participated in covered transportation and housing in addition to providing a stipend), and they often hold a capstone conference or poster session at the end where you can gain valuable experience in presenting your research.

Being an undergraduate researcher has been and still is a rewarding adventure. I feel so lucky to have incredible mentors and intriguing projects that inspire me to continue doing research in the future. I think if you’re open to different projects and patient with yourself in the lab, undergraduate research can be a really neat experience.

Finding your way into and around a lab

I started doing physics research as an undergraduate at West Virginia University. I was fortunate enough to be recruited to a plasma physics lab, where I worked on space plasma physics. I spent one summer at Los Alamos National Lab, and another summer at the Maria Mitchel Observatory, where I worked on an astronomy project. These experiences gave me a deepened understanding of physics, and helped to propel me towards grad school at Berkeley. Though the research path I chose in grad school, nanoscale physics, is different from my undergrad research projects, I appreciate having tried different kinds of research. Physics is such a basic science that a lot of the physics that applies to space plasmas also applies to nanoscale objects.

One of the most rewarding aspects of being a physics student is doing physics research. Oftentimes, crazy stuff that you learn in classes only makes sense for the first time when encountered in the lab. Participating in research can help you decide if you want to go to grad school, and if you do, the research experience will help you to have a stronger application. In order to find research projects as an undergrad, however, you will have to be comfortable being a self advocate.

The best way of starting the process of finding a research position is to talk to as many professors and grad students as you can. Go to your professors’ and GSIs’ office hours, and after getting your homework questions answered, ask about their research. If you know any other grad students, start conversations with them about research. You can also go talk to professors you don’t have a class with — most will make an appointment to talk with you and will be happy to talk about the research in their labs. Experimentalists in particular often need students to help out on small projects, but if you have coding skills then you might also have luck approaching the theorists. Just as platforms like non Gamstop casinos UK succeed by encouraging direct user engagement outside traditional frameworks, you’re more likely to find opportunities by engaging in person rather than relying solely on emails. Don’t be discouraged if you email professors and don’t get a response — there could be many reasons why you don’t get an email reply. Talking with professors in person is often more productive.

Have an open mind about the kind of research projects you’d be willing to take on, since it can be hard to know what kind of research you like until you have a bit more experience.

Expect that when you’re working on your projects in the lab that you will work most closely with a grad student, but don’t be afraid to talk to the research group professor, and participate in group meetings. Building a good relationship with your research professor is important. Another important skill for undergraduate researchers to have is the willingness to ask questions. Grad students expect that their undergrad students will have questions, and the only way to grow as a researcher is to ask those questions. And if you make mistakes, remember that it’s ok. Everybody does. Sometimes good science can come from “mistakes”.

Finally, like Compass, consider the research group a community. Try to get to know this lab community, and take your place as a young researcher.

Learning to Teach with Slinkies

Teaching can become a very structured and repetitive process if you let it. In the intro to mechanics for life-science majors course I teach during the semester, the same topics are covered every semester. Students always have the same difficulties, and much of the work I have done in previous semesters can be used in the following semesters. This might present itself as an opportunity for self-reflection and improvement, but what usually happens is that there is so much material to cover and test score are so highly valued compared to any long term improvement that my lesson plans do not evolve much.

Teaching for the Compass Project summer program 2012 exposed me to a complete change in the paradigm within which I teach. In the Compass summer program, the curriculum changes every year. This means there is very little time for curriculum refinement and we only get one chance to do it right (which we don’t always do!). At the same time, there are no exams or topics that need to be covered. The lack of constraints on the summer program teachers allowed us to develop an entire curriculum based on our own interests and values.

Calvin, Punit, Ryan, and I choose to develop a curriculum based on using the falling slinky experiment as a framework to understand how to build models in physics. This was inspired by a recently popular youtube video of a slow motion slinky drop. We had our students develop two models of a falling slinky: a discrete model that took advantage of breaking the continuous slinky into simpler masses on springs that could be understood by forces and a continuous model where they could understand the motion of the slinky in terms of waves on the medium of the slinky’s coils. The students’ models gave them useful insights into the mechanics of a slinky drop.

During the last few days of the program, the students either investigated some question that extended their model of the slinky or came up with new behavior to model or interpret experimentally. I was impressed with the students creativity and ambition on the final projects. The result of the project are four interesting videos that have been posted on the Compass youtube channel. The end of the summer program left me proud of all of the concepts, both physical and metacognitive, that our students had begun to master. I’m very excited to continue to be involved in curriculum development and teaching within Compass.